Oh-so minimal GraphQL API example with Apollo Server

Nov 16, 2020 07:48 · 1845 words · 9 minute read

Introduction

GraphQL is a query language for APIs designed by Facebook and intended as a replacement for REST. Apollo Server is a community maintained open-source server designed for GraphQL that runs on node. This post is a really minimal example of getting Apollo Server running - just so one gets a feel for the core parts. I’m therefore using a simple json flat file as a data store, and querying that with JavaScript; this isn’t a particularly realistic GraphQL use case, but it is deliberately vanilla so as not to distract.

All code can be downloaded from my minimal-graphql-apollo-server repository. This worked example requires NodeJS, if you haven’t installed it I’d recommend doing so following this StackOverflow answer.

I’m running Ubuntu 20.04.1 (Regolith flavour), Node 15.2.0, GraphQL 15.4.0 and Apollo Server 2.19.0.

Initialisation

At the terminal create a directory, and install the relevant software:

mkdir minimal-graphql-apollo-server

cd minimal-graphql-apollo-server

npm init -y

npm install apollo-server graphql

The data

We need some data to query so create a file named db.json and insert the following text (I’m taking my inspiration from There was an old lady who swallowed a fly):

{

"beasts": [

{

"id": "md",

"legs": 6,

"binomial": "Musca domestica",

"commonName": "housefly",

"taxClass": "Insecta",

"eats": [ ]

},

{

"id": "nr",

"legs": 8,

"binomial": "Neriene radiata",

"commonName": "filmy dome spider",

"taxClass": "Arachnida",

"eats": [ "md" ]

},

{

"id": "cc",

"legs": 2,

"binomial": "Corvus corone",

"commonName": "carrion crow",

"taxClass": "Aves",

"eats": [ "nr"]

},

{

"id": "fc",

"legs": 4,

"binomial": "Felis catus",

"commonName": "cat",

"taxClass": "Mammalia",

"eats": [ "cc", "nr" ]

}

]

}

The server

Create the file index.js and paste the following, which is responsible for the server itself:

const { ApolloServer } = require('apollo-server');

const { typeDefs, resolvers } = require('./schema');

const server = new ApolloServer({ typeDefs, resolvers });

// The `listen` method launches a web server.

server.listen().then(({ url }) => {

console.log(`Server ready at ${url}`);

});

Schemas and resolvers

Before we get on with the meat of the example it is worth briefly covering two of the most important concepts within GraphQL:

- Schemas (referred to as

typeDefsbelow). This defines the objects the queries will be calling and includes what types make up the object (e.g. integer, string, etc). - Resolvers. As GraphQL is essentially a query layer sitting on top of a data store (for instance a SQL database), this is the interface where we access the datastore so returning the schema above. In the case of a SQL database this might be made up of SQL statements (or a reference to a file that did contain those statements).

Schema.js

We create the schema and resolvers by pasting the following into a new file named schema.js:

const { gql } = require('apollo-server');

const db = require('./db.json');

// The statements within quotes are used by GraphQL to provide

// human readable descriptions to developers using the API

const typeDefs = gql`

type Beast {

"ID of beast (taken from binomial initial)"

id: ID

"number of legs beast has"

legs: Int

"a beast's name in Latin"

binomial: String

"a beast's name to you and I"

commonName: String

"taxonomy grouping"

taxClass: String

"a beast's prey"

eats: [ Beast ]

"a beast's predators"

isEatenBy: [ Beast ]

}

type Query {

beasts: [Beast]

beast(id: ID!): Beast

calledBy(commonName: String!): [Beast]

}

type Mutation {

createBeast(id: ID!, legs: Int!, binomial: String!,

commonName: String!, taxClass: String!, eats: [ ID ]

): Beast

}

`

const resolvers = {

Query: {

// Returns array of all beasts.

beasts: () => db.beasts,

// Returns one beast given ID.

// Underscore in the arguments is required and

// refers to 'parent', see:

// https://www.apollographql.com/docs/apollo-server/data/resolvers/#resolver-arguments

beast: (_, args) => db.beasts.find(element => element.id === args.id),

// Returns array of beasts where commonName matches

// partial string.

// 'Args' argument is destructured here,

// e.g. curly brackets means we don't have to write

// 'args.commonName'

calledBy (_, {commonName}) {

let namedBeasts = [];

for (let beast of db.beasts) {

if (beast.commonName.includes(commonName)) {

namedBeasts.push(beast);

}

}

return namedBeasts;

}

},

Beast: {

// Returns an array of beasts eaten (e.g. prey).

// This is a field corresponding to an array of IDs

// within db.json; so this matches those IDs to Beast

// objects and then returns those objects as an array.

// Parent argument is beast that API is currently

// focussed on e.g. housefly.

eats (parent) {

let prey = [];

for (let eaten of parent.eats) {

prey.push(

db.beasts.find(

element => element.id === eaten));

}

return prey;

},

// Returns an array of beasts that eat a given beast

// (e.g. predators).

// This is NOT a field within db.json, so

// involves calculating from list of prey within db.json.

// i.e. if x eats y, then y isEatenBy x.

isEatenBy (parent) {

let predators = [];

for (let beast of db.beasts) {

let predatorId;

for (let eaten of beast.eats) {

if (eaten === parent.id) {

predatorId = beast.id;

}

}

if (predatorId) {

predators.push(

db.beasts.find(

element => element.id === predatorId));

}

}

return predators;

}

},

// Adds (and returns) new beast created by user.

// As this is a minimal example it does not save to

// db.json. As it is in memory only will delete

// on node restart.

Mutation: {

createBeast (_, args) {

let newBeast = {

id: args.id,

legs: args.legs,

binomial: args.binomial,

commonName: args.commonName,

taxClass: args.taxClass,

eats: args.eats

}

db.beasts.push(newBeast);

return newBeast;

}

}

}

exports.typeDefs = typeDefs;

exports.resolvers = resolvers;

The first section of this code, typeDefs, defines the schema we will be using. It starts with our primary object: Beast. The statements within quotes are free text - and can be skipped - but serve to make the lives of other developers (and you when you are reading your code months later) easier, by providing human readable descriptions of the fields. The majority of the fields in Beast are self-explanatory - they correspond exactly to the fields in db.json. The one exception however is isEatenBy, if you examine db.json you will see this is not present. We will therefore have to construct a resolver to implicitly tell the API what a beast is eaten by (logically we know this information - the database does have an eats field, and it follows that if x eats y, then y is eaten by x).

After our Beast object is Query. This shows we have three ways of querying this information:

beastswhich returns an array of all beasts in the data store.beast(id: ID!)which returns one beast only which we look up by ID, the exclamation marks present indicates that the argument is mandatory.calledBy(commonName: String!)which returns an array of beasts where the string we provide matches their common name - e.g. ‘ca’ would match both ‘carrion crow’ and ‘cat’.

The last section of typeDefs is Mutation - this is the part of the schema which allows us to add to the datastore, rather than just query it.

The next variable in the code is resolvers which is broken into three sections:

Query. This provides the JavaScript code for querying the data store when any of the defined queries are called. For instance the first querybeastssimply returns an array of all beasts from db.json.Beast. GraphQL is smart enough to realise that when you callbeastsand ask forlegsto be included within that data, all it has to do is look for the field namedlegswithin db.json. But some queries are more difficult. For instance when we look upeatswe don’t particularly want, for example,ccreturned (which is one of the corresponding values within db.json) but rather the Beast object that represents the carrion crow. LikewiseisEatenBydoes not even have a field within db.json so we have to write logic that will return a Beast object when the API is asked.Mutation. Lastly we have the JavaScript telling the API how to add new information to the dataset. Of note is that this function also returns the Beast object just added; this allows the user to immediately see the information that they have added.

Start the server

Explanations over, let’s start the server. At the terminal enter:

node index.js

Assuming success you should see a message similar to the following:

Server ready at http://localhost:4000/

Playground

Pointing your browser at the URL given above you should now see the built-in playground where you can test your API.

Below the statement #Write your query or mutation here enter the following query:

{

beasts {

commonName

legs

}

}

If everything has worked you should see the following response:

Arguments

The resolvers we have built also allow us to supply arguments to define our search, so entering:

{

beast(id: "cc") {

commonName

taxClass

}

}

Will pull up data on the crow only:

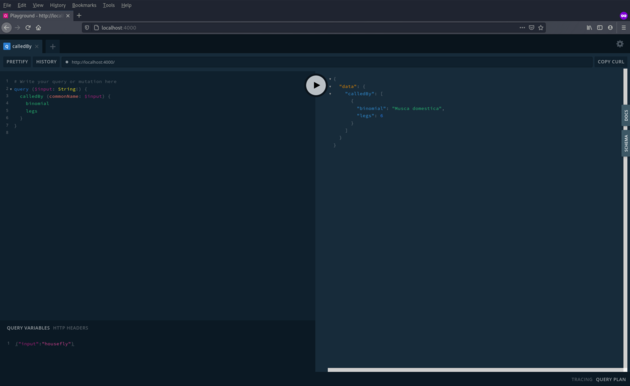

Query variables

Using our API for real we will likely not be hardcoding an argument directly into the query so the Query Variables section of the playground allows us to add variables in a similar way as to how we might via a web page (e.g. a form). To use this enter in the main query section:

query($input: String!) {

calledBy(commonName: $input) {

binomial

legs

}

}

then in the Query variables field found at the bottom of the browser window enter the variable as so:

{"input": "housefly"}

which should result in the following:

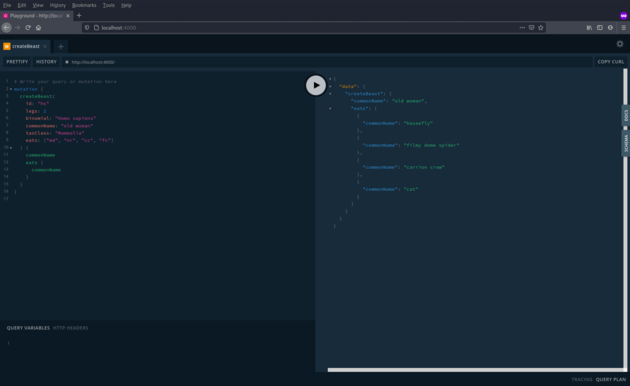

Mutations

So far we have just been querying the data, we can also amend it via a mutation.

Our data set is missing some information; the old woman who has eaten all of these creatures. Therefore in the playground enter:

mutation {

createBeast(

id: "hs"

legs: 2

binomial: "Homo sapiens"

commonName: "old woman"

taxClass: "Mammalia"

eats: ["md", "nr", "cc", "fc"]

) {

commonName

eats {

commonName

}

}

}

Success that the data has been entered should appear with a list of the beasts the poor lady has eaten:

As this is a minimal example this mutation is in-memory only and isn’t saved to disk (i.e. the db.json file) - if you restart the server the data will be erased.

Alternative server start

The disadvantage to starting the server with node index.js as above, is that every time you make a change to the source code (like add a new resolver or amend the schema), you have to restart from the command line. Alternatively if you start the server with:

npx nodemon index.js

your code will be monitored and the server will restart automatically. Will save you lots of time if you are making frequent changes.

Conclusion and Further reading

If you have found this useful, or have feedback, then please let me know in the comments. Further reading on this can be found at:

- Introduction to Apollo Server. The definitive guide.

- Introduction - Apollo Basics. More of the same but this is the complete full stack walk through which queries live data.

- Learn to Build a GraphQL Server with Minimal Effort. Another useful light-weight demonstration, although with a more realistic back end than our db.json as it interfaces with a mock REST API.